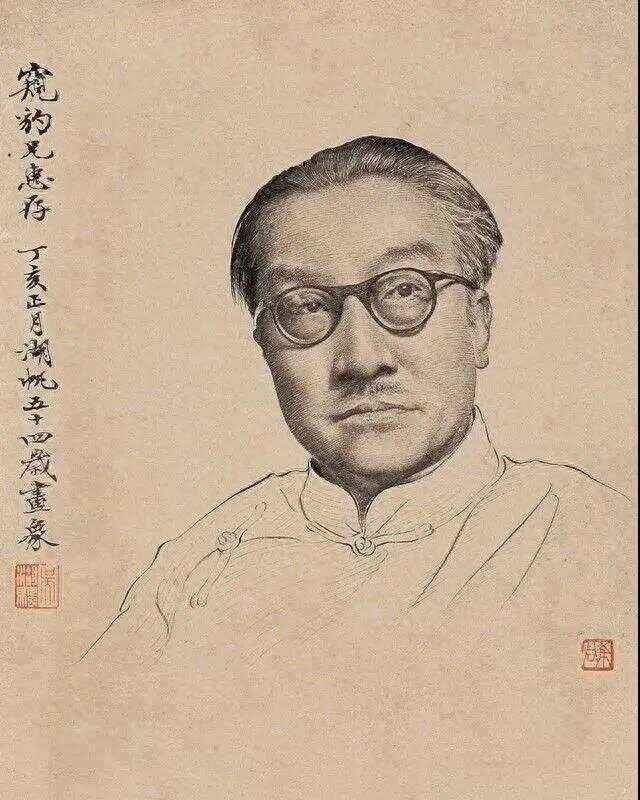

Wu Hufan

CN

209

Artworks

1894 - 1968

Lifespan

Artist Biography

Wu Hufan (1894–1968) stands as one of the most significant figures in 20th-century Chinese art, revered as a master painter, authoritative connoisseur, avid collector, and influential educator. Born in Suzhou to a distinguished literati family, his heritage was steeped in art and scholarship. His grandfather, Wu Dacheng, was a celebrated official, calligrapher, and collector, providing the young Wu Hufan with unparalleled access to a vast collection of classical paintings and artifacts. This immersive environment established the foundation for his lifelong dedication to China's orthodox painting tradition. From his earliest years, he studied the masters, beginning with the Four Wangs of the Qing dynasty and later delving into the works of Dong Qichang and the earlier titans of the Song and Yuan dynasties.

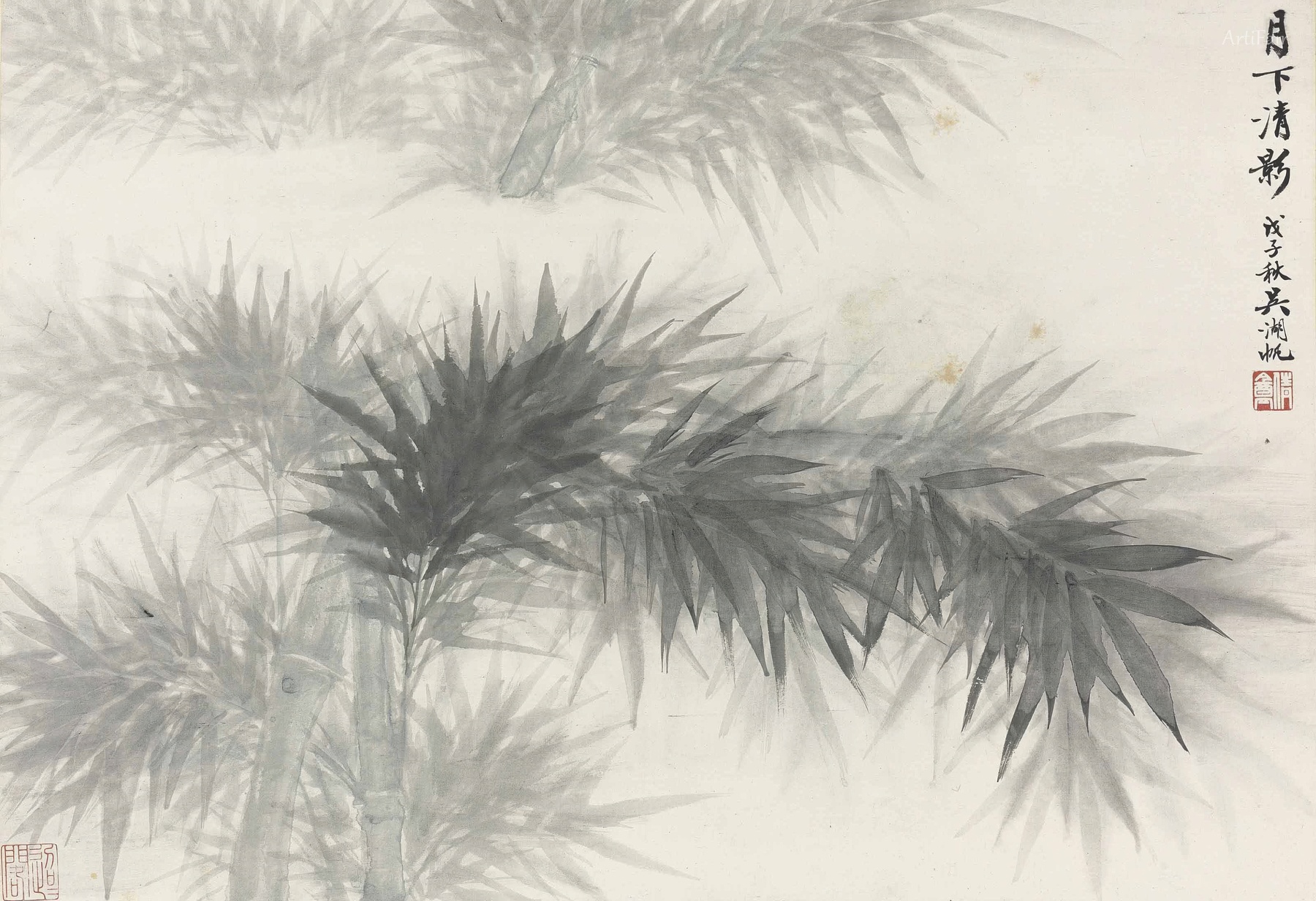

After moving to the vibrant metropolis of Shanghai in 1924, Wu Hufan's reputation flourished. His artistic practice was characterized by a profound synthesis of historical styles, notably his effort to harmonize the Southern and Northern schools of landscape painting. He developed a signature aesthetic known for its elegant brushwork, delicate ink tones, and sophisticated use of color, particularly a technique that combined rich ink washes with mineral-green pigments. While landscapes were his primary focus, he also excelled in painting bamboo and flowers. His mastery earned him widespread acclaim, with the famed artist Zhang Daqian praising him as "the first person in the painting circle of the Republic of China." His work, deeply rooted in tradition, remained a sanctuary of classical beauty, conspicuously avoiding the turbulent political themes of his time.

Wu's role as a connoisseur and collector was as influential as his painting. His studio, the "Meijing Bookstore" (梅景書屋), became a legendary hub for artists and scholars. His collection was legendary, most famously including the "Remaining Mountains" scroll, a fragment of Huang Gongwang's masterpiece "Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains." His expertise was so respected that he was appointed a committee member for the Palace Museum, helping to select national treasures for international exhibitions. Wu was not merely a passive owner of art; he was an active scholar, writing extensive colophons on his pieces. These writings combined traditional connoisseurship with a strikingly modern, analytical approach, challenging and expanding the genre and solidifying his role as a guardian of China's cultural legacy.

As an educator, Wu Hufan's influence extended to a new generation of artists and scholars. At his Meijing Bookstore, he mentored a group of disciples who would become major figures in their own right, including Xu Bangda, Wang Jiqian (C.C. Wang), and Lu Yifei. His teaching method was student-centered, focusing on cultivating individual talent while ensuring a rigorous grounding in classical techniques. After 1949, he continued to teach at the Shanghai Institute of Chinese Painting, further cementing his legacy as a pivotal link between China's imperial past and its modern artistic future.

The establishment of the People's Republic of China in 1949 brought profound challenges. While Wu publicly declared his support for the new regime, his personal life and artistic pursuits remained largely aligned with the displaced literati culture. He became an unwitting spokesperson during the "Sandalwood Fan Incident," advocating for artists struggling financially, which drew unwanted political attention. His proud refusal to engage in self-criticism during this period likely cost him the directorship of the Shanghai Chinese Painting Academy. The Anti-Rightist Campaign of 1957 intensified this pressure, and he was heavily criticized for his past and his perceived bourgeois lifestyle. The ordeal was so severe that his son reportedly took the political blame to shield him.

The immense political and psychological stress took a heavy toll on Wu's health, culminating in a stroke in 1961. In his final years, his art underwent a fascinating transformation. He began practicing the wild, cursive calligraphy of the Tang dynasty monk Huaisu, a style greatly admired by Chairman Mao. This shift has been interpreted as both a final, profound artistic evolution and a pragmatic political adaptation to a hostile environment. During the chaos of the Cultural Revolution, with his collection confiscated and his spirit broken, Wu Hufan tragically took his own life in 1968. His death marked the somber end of an era, but his legacy as a monumental painter, scholar, and cultural conservator endures.